The Alpaca Digestive System

Feeding llamas and alpacas is a complex subject. It’s best to discuss the matter with your county extension agent or a livestock nutritionist in your area. Every farm is different so you need to be thorough about your own farm and amenities. However, certain truths apply no matter where you live or what sorts of llamas or alpacas you feed.

Whatever you feed your herd, dietary changes must be made over a period of time: 10 -14 days is sufficient. Abrupt changes trigger potentially life-threatening digestive upsets. Also, establish a routine and stick to it. Don’t stress your llamas and alpacas by skipping or delaying their meals. Make certain each animal is eating. Alpacas that refuse their usual feed are probably ill.

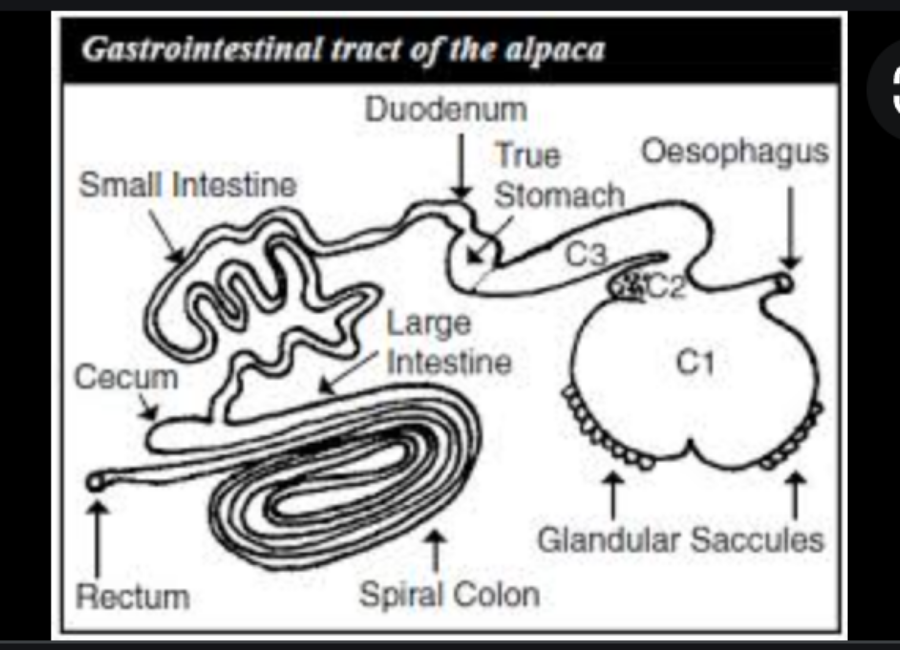

Alpacas are modified ruminants. Their forestomachs are made up of three compartments rather than the true ruminants’ (sheep, goats, cattle, deer) four. Whether 3 or 4 compartments, ruminants’ digestive systems are very unlike those of simple-stomached species such as horses, carnivores and humans. The three sections of alpacas’ forestomachs are called C-1, C-2 and C-3; each compartment has a specialized job to perform.

C-1, located on the animals left side, is the largest (and first) compartment; it makes up roughly 80% of the stomach’s total volume. C-1 secretes no digestive enzymes – it’s essentially a fermentation vat housing a horde of friendly microorganisms that convert cellulose into digestible nutrients. Newly eaten feed liberally mixed with saliva comes into C-1 by way of the esophagus, then fermentation begins. Corse bits of feed are periodically regurgitate, rechewed and then reswallowed, a process know as rumination or chewing the cud. Additional chewing reduces particle size and churns in more saliva, important because saliva adds bicarbonate and phosphate buffers to combat acid production during fermentation. The average healthy alpaca ruminates about 8 hours a day.

Ingested material stays in C-1 for roughly sixty hours, where it is continually mixed by strong, spontaneous contractions of the forestomach. The material next moves into C-2, where some absorption of nutrient occurs, and then on it goes into compartment C-3.

C-3 is a tubular organ running along-side C-1 on the right side of the abdomen; it holds 11% of the forestomach volume. The last 1/5 of this tube contains true gastric glands, so C-3 is sometimes called the true stomach. Stressed alpacas frequently develop ulcers in C-3.

Further digestion occurs in the small intestine. Material then presses on to the cecum and spiral colon, where vitamins, minerals and water are absorbed and fecal pellets are formed of the remaining waste and eventually eliminated.

In newborn crias, only the true stomach is fully functional. However, as it suckles its dam and begins nibbling plants, a cria ingests the microbes needed to kick-start C-1 function. By 8 weeks of age, the alpaca’s C-1 reaches adult size, and by 12 weeks, the animal is functioning like a grown-up alpaca. Thus, if the cria is no longer able to nurse from the mother, it will survive. However, separation too soon can have an emotional impact. That is why we separate and wean our cria at 6 months of age.

Camelids, particularly llamas, are far more efficient rough-pasture feeders than are cattle, sheep, and even goats. They consume 20 to 40 percent less feed per unit of metabolic body weight that sheep do on the same diet, primarily because alpacas produce more saliva in relationship to foregut volume than sheep and goats do. The pH of C-1 is closer to neutral which favors cellulose-friendly microbes and enhances fiber digestion. Digestive matter remains in C-2 longer, allowing microbes to process more fiber; blood nitrogen is extracted from the kidneys and used more efficiently in llamas and alpacas; and liquid passes more rapidly through the camelid gut.

Support Alpacas of Montana by sharing our articles and shopping our products!

Join the alpaca revolution! Alpaca is a sustainable alternative that is not only good for the earth, but for all of us. Alpaca wool is stronger, softer, more eco-friendly, and offers 85% greater wicking capability than merino wool. It is also hypoallergenic! Learn more about the benefits of alpaca in our Alpaca vs. Wool blog posts, shop our collections and follow us on social media!